MUSIC: COMPOSING A CLASSICAL MIRACLE

BY CHRIS PASLES, NOV. 9, 1994 (LA Times)

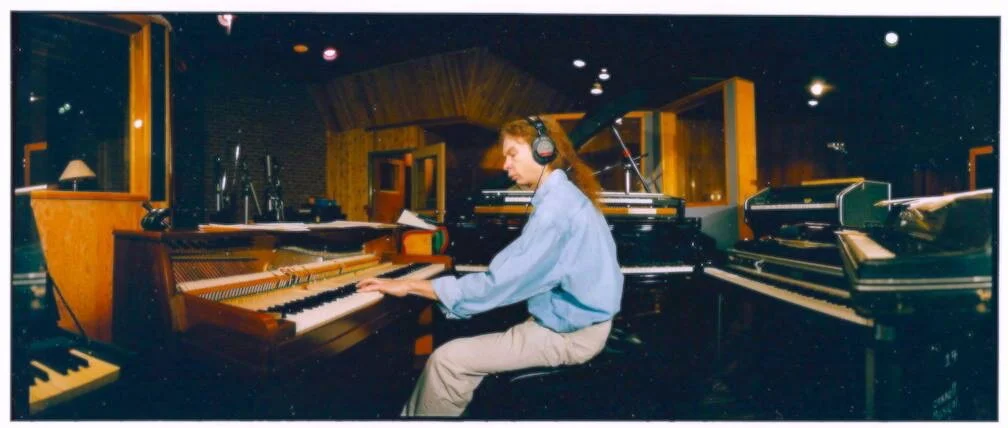

Crossing between two music worlds isn’t such a stretch, jazz composer and keyboardist Lyle Mays says.

“They’re not all that different--jazz and classical music,” Mays said in a recent phone interview from his home in Wisconsin. “There is a huge difference between a jazz player and a classical player, but I don’t think there is much difference between a jazz player and a composer.

“A good (jazz) player has to come up with compositions on the spot. In classical, there are questions of making it more formal--and there are a ton of other differences--but I think the leap is less in composition than in performance.”

Composition and performance will be on display Thursday at the Orange County Performing Arts Center when Mays’ latest classical piece, “Twelve Days in the Shadow of a Miracle,” gets its premiere by the Debussy Trio, which commissioned it. The title stems from the long personal crisis in Mays’ life that inspired it.

“Our family was experiencing a lot of difficulties,” Mays, 40, said. “My partner’s father had a crisis with Parkinson’s disorder. At one point in the middle of this crisis, he had a marvelous recovery with some drug therapy. It reminded me very much of what (neurologist-author) Oliver Sacks wrote about in ‘Awakenings.’ I was struck how he described these recoveries as miraculous. It was one of the few times that he felt the word could be used in modern medicine.

“It was quite an event. So I felt this was indeed miraculous. It affected us all.”

To try to capture that sense of the miraculous, Mays tried to structure the work, he said, “like the way life unfolds. The form is not chaotic. It has a kind of organization like our lives have organization. Some things recur, some go away and we never see them again. It’s a combination of natural forms and patterns that emerge.”

“Like the way life unfolds. The form is not chaotic. It has a kind of organization like our lives have organization. Some things recur, some go away and we never see them again. It’s a combination of natural forms and patterns that emerge.”

His own life has followed what he calls “a very natural progression into jazz.” He was born and raised in northeastern Wisconsin. “Wausaukee was the nearest town. It had 500 people. We were 15 miles away from that.” His father had taught himself to play guitar and to sing. His mother played organ and piano for the church. They created an environment that encouraged his fooling around on piano.

“For me, jazz was a very natural progression. The more I got into music and played, the more it was natural to play and embellish things. The embellishments got more elaborate. I was never stopped. I was always encouraged.”

He began going to summer jazz camps and festivals, eventually meeting guitarist Pat Metheny in Wichita in 1975. The two didn’t get a chance to play together until a year later in a small club in Boston.

“Things just clicked from the first tune we played,” Mays said. “We vowed to do something. Shortly thereafter, he formed a band in Boston. I thought he was kind of nuts. We were just kids. I didn’t think he could make a go of it. But it worked and has been working ever since.”

In addition to his work with Metheny, which has brought them a number of awards, including several Grammy nominations, Mays has toured with jazz singer Bobby McFerrin and recorded with singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell and others. He began composing for PBS television shows and Hollywood films in the early ‘80s and soon began getting serious about writing classical chamber-music pieces.

“I was toying with the idea all through the early part of the ‘80s,” he said, “studying, researching, sketching. Among musicians,” he added, “there is this thought that there is good music and (there is) other music. The style question isn’t all that big a deal.”

The Debussy Trio commission, however, posed a challenge because of the group’s uncommon combination of harp, flute and viola. He had never written for harp.

“I decided I had to take some harp lessons,” he said. “It’s played so differently from a piano; I felt I had to know a lot more about it before I could write for it.”

Mays also started experimenting in playing on a keyboard and recording the results directly into his computer. “I can manipulate (my ideas) much faster, getting improvisational in the process” that way.

It also led to some new problems.

“It was going really fast and furious; I was really happy with the results. Then I realized that, other than a few sketches, I had nothing written out, and the piece was getting rather large.”

To solve the problem, he contacted a friend who told him about a program that was supposed turn music recorded in the computer’s memory into a printed score.

“Well, it turned out a raw mess,” Mays said. “Computers are stupid. They interpret things literally. If I would play in an arpeggio, the computer would print out a (smear). Well, in writing for a harp, there are lots of arpeggios.”

Still, he feels that the process was worth it because the result “is a pretty true representation of what I was hearing. I didn’t change it putting it down on paper. It never got simplified inadvertently or made complicated inadvertently.

“The process of translating music ideas to paper and then getting them interpreted again is a two-stage process where things can go wrong. Things may get improved, but composers can go wrong.”

Even so, “the piece is not ever finished until the composer and the players get together and play it. That’s the last stage of editing. I always heard that (Claude) Debussy never finished his pieces. There were complaints about that back then. So if we don’t do all the editing now, it will still be in their namesake’s tradition.”

(Courtesy of LA TIMES)